Maas Roy’s award (Windrush)

In 1954, Stanley Roy Archer departed Jeffrey Town, St Mary, and headed to England, then seen as ‘greener pastures’, to earn an honest living to take care of his family. He ended up being caught in the rip-stream of what became known as the Windrush Generation.

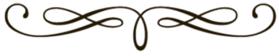

Maas Roy shows an army photo from 1954, at the vice-chancellor’s forum on the Empire Windrush held at the UWI, Mona campus. Mr Archer is standing on the left in the photo.

The Gleaner, 17 May 2018, Paul Clarke

“I worked hard to better my family situation while in St Mary, but when it came to the crunch, I had to go to greener pastures, and the greener pastures at the time was England, and it was easy to get there,” Archer recounted.

“So I went off to England in 1954 as a tradesman to earn an honest living for my family back here in Jamaica,” he said.

He was relating his tale to a group of academics, including former Prime Minister Bruce Golding, during The University of the West Indies (UWI) Vice-Chancellor’s Forum under the heading ‘Empire Windrush – Migration, Exclusion and Compensation’ on Tuesday at the UWI Regional Headquarters.

Archer would go on to serve in the British Military after being in England for two years, making him eligible for enlistment. He was subsequently posted in Cyprus, but his heart was always in Jamaica.

He was unable, however, to escape the shocking social injustice and racism that marked the typical British life during that time, explaining that it was difficult being black in England as they were often viewed as equal to dogs in certain places.

“Living in England at that time was always an uphill battle. There were some physical fights that had to be fought, and black people could not venture down certain streets because of serious racism. There were signs on doors that read ‘No Irish, No Blacks and No Dogs’. Those were some of the things we had to put up with while there,” Archer told The Gleaner.

To prove citizenship, Archer produced his passport, still in immaculate condition, issued on September 17, 1954, and signed by Colville Montgomery Deverell, the colonial secretary at that time.

“We went over there as citizens but got treated like animals. It was wretched for many of us, but we worked hard,” Archer recalled.

“It was so dreadful that I felt at the time that if I could put two flappers on a bicycle, I would use that bicycle to get back to Jamaica. It was so depressing; it was so uncomfortable until I ended up in the military service. They called it the national service,” he said.

He said that Jamaicans who went to England during that period, and successive generations, had no proper documents and that passports, which were issued under the authority of the Crown, giving them citizenship, meant nothing.

“The first generation of the parents who went there got no papers. They had no status. They were just another body. Even now, I can tell you that persons wishing to go to university are being turned down because a search through their family background revealed they had no documentation of citizenship after so many years,” Archer disclosed.

“Windrush for us was just a ship transporting people from other parts of the Caribbean and Jamaica to England. I could not understand what the Windrush Generation meant because it was before some of us went to England,” he said.